Why Genius Was a Liability for Heian Women

At the Heian court, brilliance was admired in principle and punished in practice. Education, poetic skill, and aesthetic intelligence were not optional accomplishments for women of rank; they were part of the labor that sustained court culture itself. Women composed poetry on demand, anchored ritual occasions, entertained guests, and embodied refinement through speech, dress, and comportment.

Yet the same system that depended on their intelligence worked relentlessly to contain it. Genius was acceptable only when it appeared modest, ornamental, and ultimately expendable. When it asserted itself too clearly—when it sounded confident rather than deferential—it became a liability.

This tension shaped women’s lives and writing in ways that are still legible a thousand years later. The Heian court prized sensitivity, timing, and taste, but it distrusted women who appeared too aware of their own mastery. A woman could be praised for her elegance, but not for her authority. She could be admired for cleverness, but not for judgment. The moment intelligence tipped into self-possession, it attracted resentment. Attention sharpened into scrutiny. Admiration curdled into moral suspicion.

Sei Shōnagon is the most visible example of what happened when a woman refused to disguise her brilliance. The Pillow Book delights in judgment, pleasure, and wit without apology. Shōnagon writes as someone who assumes her perceptions are worth recording and her tastes worth asserting. That confidence is precisely what unsettled her contemporaries and later readers. She was accused of arrogance, cruelty, and vanity, charges that have clung to her reputation for centuries. What provoked these reactions was not merely what she said, but how easily she said it—how little she softened her intelligence into humility.

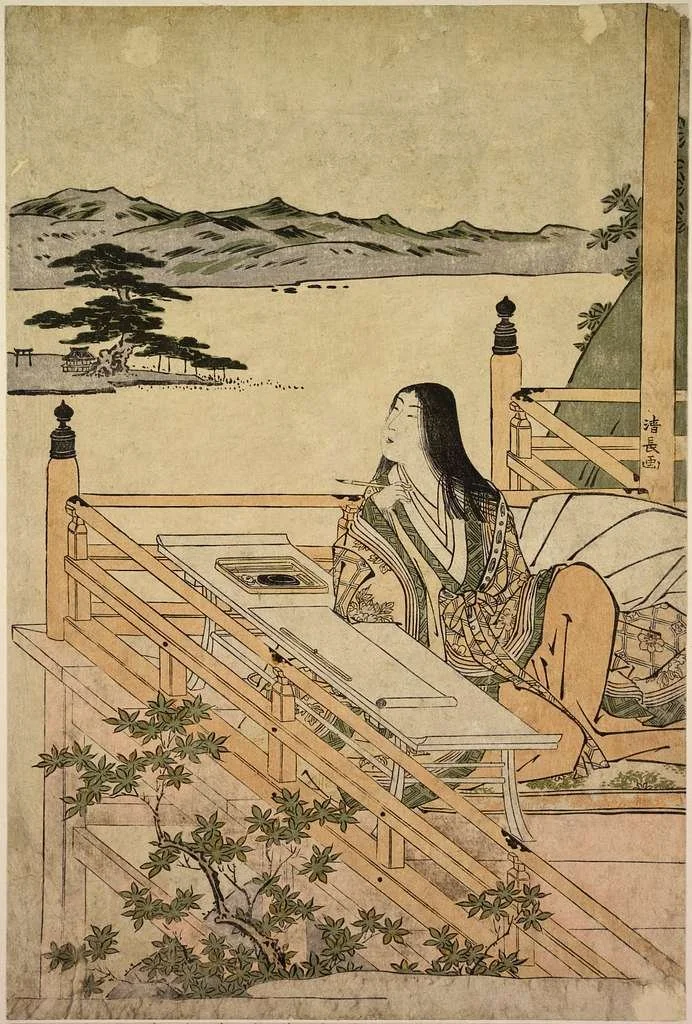

Murasaki Shikibu watched this and chose another strategy, but she paid a different price. Her learning was formidable, her command of Chinese literature unusual, her narrative imagination unprecedented. She understood, however, that brilliance could not appear unguarded. Her diary records a woman constantly regulating herself, aware that visibility invited punishment. She criticizes Sei Shōnagon not out of petty rivalry, but out of fear. To Murasaki, Shōnagon’s ease looked like miscalculation in a world that did not forgive women who seemed too pleased with themselves. Murasaki’s restraint was not timidity; it was survival.

Even restraint, however, did not protect her. Her intelligence isolated her. She was admired, resented, watched. The very brilliance that produced The Tale of Genji—a work of astonishing psychological depth and narrative scope—also made her wary of exposure. Genius did not liberate her. It sharpened her awareness of danger.

Izumi Shikibu offers yet another version of this pattern. Her poetic brilliance intensified her erotic visibility. Her talent made her desirable, and her desire made her vulnerable. She was celebrated and condemned in equal measure, praised for her poetry and punished for the life that poetry made legible. Her genius did not excuse her transgressions; it amplified them.

What unites these women is not temperament, but structure. The Heian court relied on women’s intelligence while denying them authority over its meaning. Genius in women was tolerated only as long as it could be framed as service or charm. Once it began to look autonomous—once it suggested judgment, appetite, or self-trust—it was met with correction.

This correction rarely took the form of formal punishment. It arrived as gossip, moral critique, social isolation, and reputational afterlife. Women were not expelled from court for brilliance; they were remembered badly for it. Their intelligence became evidence against them, recast as arrogance, excess, or emotional instability.

The tragedy is not that Heian women were discouraged from genius, but that they were encouraged to cultivate it and then punished for possessing it too openly. The literature they left behind records this contradiction with devastating clarity. Their brilliance survives because it was written under pressure, shaped by vigilance, and sharpened by consequence.

To read Heian women’s writing is to encounter not only extraordinary talent, but the cost of having it in a world that demanded refinement from women while resenting their authority. Genius was not a path to safety. It was a risk—and these women knew it.