Writings on the Heian Court

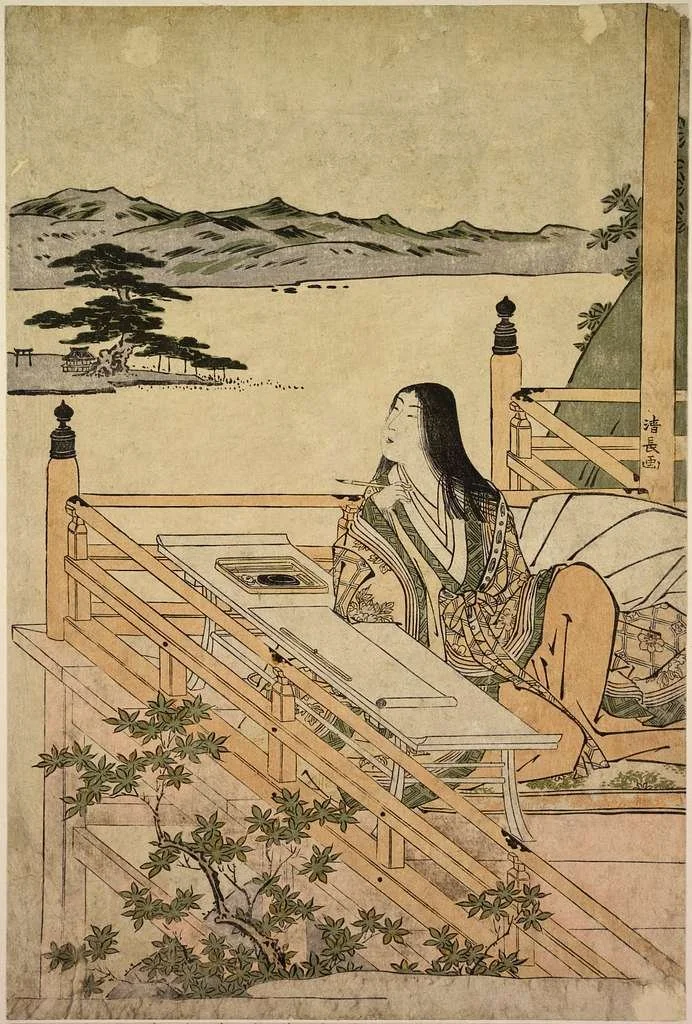

The Heian court was a world where power moved through proximity, desire through poetry, and reputation through rumor. Writing was not decorative but dangerous—a way to register intimacy, faith, and survival under constant observation. This page explores Heian literature as lived experience, returning to writers such as Murasaki Shikibu, Sei Shōnagon, Izumi Shikibu, and the Sarashina diarist not as distant classics but as architects of a refined and unforgiving social world. Their texts do not simply record court life; they reveal how court life shaped attention, sexuality, faith, and the conditions under which a woman could speak. The Tale of Genji is read here not as romance but as an anatomy of power and impermanence, while the diaries are approached as acts of judgment and self-preservation, where poetry circulates as evidence, genius becomes a liability, and Buddhism functions as consolation and threat rather than doctrine.

Why The Tale of Genji Is Not a Romance

Why The Tale of Genji is not a romance. This essay examines power, consent, harm, and impermanence in Murasaki Shikibu’s novel, showing how desire operates through inequality and Buddhist impermanence, leaving women to bear the lasting consequences of attachment.

Why Genius Was a Liability for Heian Women

Why genius was a liability for women in Heian Japan. This essay explores brilliance, resentment, and gendered punishment through writers like Sei Shōnagon, Murasaki Shikibu, and Izumi Shikibu, revealing how female intelligence was cultivated, constrained, and socially penalized at court.

Examining the Genji Translations

A comparative essay on English translations of The Tale of Genji examines Suematsu, McCullough, Washburn, Seidensticker, Waley, and Tyler, showing how style, fidelity, and scholarly approach shape modern readings of Murasaki Shikibu’s classic, with a personal case for Washburn’s version.