Erotic Pedagogy: Sex as Moral Formation Among Samurai

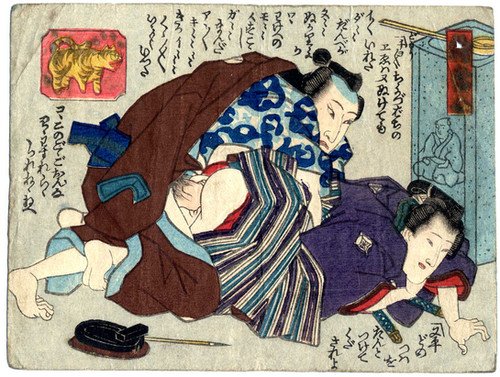

In later medieval and early early-modern Japan, sex between men was not understood primarily as indulgence, deviation, or private preference. Within warrior culture, it was often framed as instruction. Erotic intimacy functioned as a mode of moral formation, one that bound younger warriors to seniors through affection, discipline, and obligation.

Desire was not opposed to ethics; it was enlisted in their production. To modern readers, this fusion of eros and morality can feel unsettling, but for the samurai world it made a certain kind of sense.

Warrior society was structured around hierarchy, loyalty, and the cultivation of character under pressure. Martial skill alone was insufficient. A warrior was expected to embody restraint, courage, fidelity, and the capacity to endure loss without collapse. These qualities were not assumed to arise naturally. They had to be trained into the body and the emotions, just as swordsmanship was trained into the muscles. Erotic relationships between men—particularly those structured by age and rank—were one of the sites where such training occurred.

The younger partner in these relationships was not simply an object of desire. He was a student, an initiate, someone in the process of becoming. The older partner bore responsibility not only for instruction in arms, but for shaping comportment, loyalty, and emotional discipline. Erotic intimacy intensified this bond. It made obligation personal. The relationship carried expectations of exclusivity, discretion, and mutual honor, all of which mirrored the broader ethical demands of warrior life.

What mattered was not sex in isolation, but the discipline surrounding it. Desire was expected to be governed, not denied. Excessive indulgence, public impropriety, or emotional volatility could undermine a warrior’s reputation. Properly conducted, however, intimacy between men was thought to cultivate attentiveness, restraint, and devotion. It taught the younger partner how to submit without humiliation and the older partner how to command without cruelty. In this sense, sex was less a release than a rehearsal.

This pedagogical framing is visible in the language used to describe such relationships. They are often discussed in terms borrowed from mentorship, service, and ethical cultivation rather than pleasure. Emotional attachment is acknowledged, even expected, but it is meant to strengthen resolve rather than soften it. Love becomes a means of binding one person’s fate to another’s, preparing both for the demands of loyalty that defined warrior existence.

Crucially, this system depended on asymmetry. Age, experience, and rank structured the relationship, ensuring that intimacy reinforced hierarchy rather than dissolving it. When those boundaries blurred—when desire threatened to overturn authority or produce dependency—the relationship became suspect. The problem was not that intimacy existed, but that it might cease to function pedagogically. Sex that no longer taught restraint or loyalty was no longer ethical.

From this perspective, the moral concern was never the gender of the participants. It was the shape of the bond. Samurai culture did not ask whether desire was heterosexual or homosexual. It asked whether it produced the right kind of person. Erotic relationships were evaluated by their outcomes: Did they strengthen courage? Did they deepen loyalty? Did they cultivate self-command? Desire that failed these tests was seen as corrosive, regardless of who was involved.

This helps explain why same-sex intimacy among warriors could coexist with marriage, concubinage, and reproduction without contradiction. These relationships occupied different moral registers. Marriage served lineage and alliance. Erotic pedagogy served formation. One was reproductive and political; the other was ethical and affective. They did not compete because they were not asked to do the same work.

It is tempting to read this system as exploitative or idealized, and at times it was both. Power differentials were real, and the language of moral formation could obscure coercion or abuse. Yet the historical record suggests that participants understood these relationships as serious commitments rather than casual encounters. Betrayal, indiscretion, or abandonment could carry lasting social consequences. The bond mattered because it was meant to shape who one became.

This seriousness distinguishes erotic pedagogy from mere tolerance of same-sex behavior. Desire was not simply permitted; it was structured, narrated, and invested with ethical significance. The samurai world did not treat sex as morally neutral. It treated it as formative. Bodies were sites of training, and intimacy was one of the disciplines through which the self was shaped.

Over time, these practices became increasingly codified, especially in the early modern period, when manuals and stories elaborated ideals of male-male devotion. Yet even as representation multiplied, the underlying logic remained consistent. Erotic intimacy was valuable insofar as it produced loyalty, courage, and restraint. When it failed to do so, it lost its legitimacy.

Seen from the present, this framework unsettles familiar assumptions about sexuality. It refuses the idea that sex belongs solely to private pleasure or personal identity. It situates desire within social obligation and moral outcome. For the samurai, sex was not an expression of who one was. It was part of how one was made.

This does not mean that warrior culture celebrated desire uncritically. Discipline was always at risk of collapse. Attachment could weaken resolve. Loss could devastate. Erotic pedagogy acknowledged these dangers even as it harnessed intimacy for ethical ends. The system assumed impermanence and vulnerability, not purity.

To understand sex as moral formation among samurai is to recognize a world in which desire was neither repressed nor romanticized. It was trained. It was shaped to serve ideals of loyalty and honor that extended far beyond the bedroom. Intimacy was not opposed to discipline; it was one of its most demanding forms.

What this history offers is not a model to emulate, but a challenge to how we think about sex and ethics. It reminds us that desire has been asked to do many kinds of work across cultures and time. Among the samurai, it was asked to make warriors—not by denying the body, but by binding it to duty, obligation, and the difficult art of self-command.