Episode IV: What Remains Unsaid

There is a particular stillness that settles after a disruption has been carefully absorbed. It is not peace. It is closer to composure—the kind cultivated through long practice, in which surfaces are smoothed before anyone is permitted to ask what has been lost beneath them.

After Izumi’s departure, the court entered such a season.

New faces appeared, as they always did. Young women arrived from promising families, their hair still arranged with a nervous precision, their poems earnest in a way that suggested faith in recognition. They learned quickly whom to watch and whom to avoid. They learned, too, that the absence of certain names was not accidental. No one instructed them. The court trained without speaking.

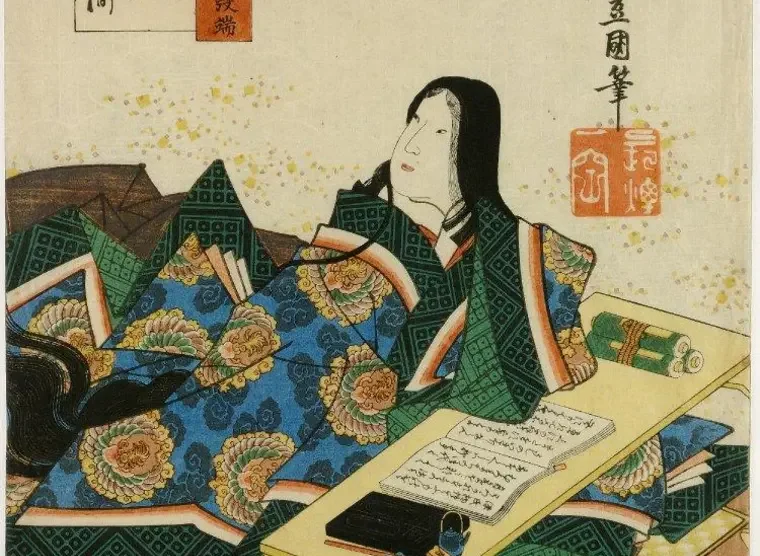

I continued my service, though the nature of it had changed. Where once I had been asked to observe widely, now I was encouraged to observe carefully. The distinction mattered. I learned to write in ways that offered texture without emphasis, to record events as if they had already receded into memory. Praise came quietly. Disapproval came not at all. I understood then that silence was no longer merely a condition of the court—it was its preferred instrument.

The empress remained composed throughout, her authority intact and unquestioned. Yet I sensed, beneath her restraint, an awareness that extended beyond immediate management. Once, during a late autumn gathering when the garden lay stripped and exact beneath the sky, she spoke to me without prompting.

“Stability,” she said, watching a servant adjust a screen, “is not the absence of disturbance. It is the careful placement of it.”

I bowed, receiving both the insight and the warning. The court did not deny upheaval. It allocated it.

Sei Shōnagon thrived under these conditions, though even she had altered. Her wit had not dulled, but it had grown more surgical, deployed only when its effect could not be misunderstood. She became, if anything, more influential—her observations circulating long after she herself had left a room. Yet I noticed that she, too, now chose silence where once she might have delighted in exposure.

“Cleverness,” she said to me one evening, “is like lacquer. Too many layers, and the object beneath disappears. Too few, and it splinters.”

“And memory?” I asked.

She smiled. “Memory is the grain. It shows through no matter how carefully one coats it.”

Letters from Izumi continued to arrive, though irregularly and without pattern. They spoke of provincial life—of lesser courts where poetry was still exchanged, though with less consequence; of evenings quieter than any we had known, where the sound of water carried without interruption. She never complained. She never asked to return.

Her poems, when they appeared, had changed. They were no longer invitations. They were statements—contained, assured, unconcerned with response.

Even far from sight,

the heart keeps its own counsel—

no gate holds the wind.

I kept these lines to myself. Not out of fear, but out of recognition. They belonged to a version of Izumi the court could no longer reach.

As months passed, I began to understand that her removal had served multiple purposes. It had satisfied the court’s need to reassert discretion. It had reassured those who mistook control for order. But it had also created something unintended: a figure no longer bound by immediate consequence, whose influence now moved through recollection rather than presence.

In this way, Izumi had become more durable than many who remained.

My own work shifted once more, though so subtly that even I did not recognize it at first. I found myself drawn to moments the court barely noticed: the hesitation before a poem was delivered, the choice of silence where speech might have earned favor, the quiet endurance of women whose brilliance lay not in provocation but in survival. I wrote about these things obliquely, trusting that those who needed to understand would do so.

Sometimes I wondered whether this, too, would one day be deemed excessive.

The thought no longer troubled me as it once might have. Izumi had taught me that removal was not disappearance, and Sei Shōnagon had taught me that memory, once sharpened, could outlast permission.

On rare evenings, when the palace settled into its deepest quiet and even vigilance seemed to sleep, I imagined a future not yet arranged. A time when words written now—carefully, incompletely—might be read differently. Not as ornament. Not as caution. But as testimony.

The court would endure. It always did. Structures persisted because they were convincing, not because they were just. New names would replace old ones. New verses would circulate, praised for their freshness, their obedience to form. The rhythm would continue.

But beneath it, something had shifted.

The women who remained had learned what it meant to be seen—and what it cost. They had learned that silence could be both refuge and weapon, that absence could generate its own authority, and that memory, once released from the body, traveled where no gate could follow.

If there is a conclusion to be drawn, I have never trusted it.

What I know instead is this: nothing truly observed is ever lost. It waits, stored in ink or breath or the careful discipline of recollection. And when the time comes—when the world grows inattentive enough—it speaks again, not loudly, but with a persistence that cannot be undone.

That knowledge did not make me bold.

It made me precise.

And in the court, precision was the closest thing to freedom we were ever allowed.