Love in the Age of Light: Homosexuality in the Belle Époque

There’s a particular light in the paintings of the Belle Époque — that soft, golden haze caught between day and night — and perhaps that’s fitting. It was an age poised between old certainties and modern desires, between repression and revelation. From roughly 1871 until the outbreak of World War I, Europe, and especially Paris, lived in the shimmer of possibility. The cafés never seemed to close; the air itself buzzed with invention — telephones, electricity, moving pictures. To be alive then was to feel the future breathing down your neck, whispering that anything was possible, even love that dared not speak its name.

I often imagine walking through Montmartre at dusk, the cobblestones damp with rain, gas lamps flickering to life. The laughter from Le Chat Noir spills out into the street. Painters and poets lean close over cheap wine, their talk full of scandal and beauty. Somewhere in that hum — in the shadows behind those velvet curtains — lived another world entirely: the hidden life of queer men and women who found in art, and in one another, a language for what society refused to name.

The Belle Époque loved appearances — corsets, manners, fine phrases — but beneath the lace and etiquette pulsed something raw and human.

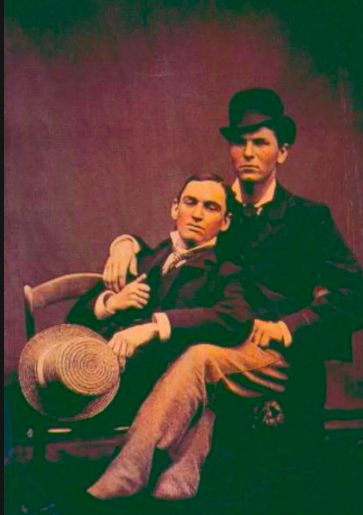

Men met in the backrooms of cafés or at masked balls where gender became costume and performance. Women found each other in salons and studios, exchanging glances that lasted longer than politeness required. Paris, in particular, was a city of permission and pretense. Homosexuality wasn’t criminalized there as it was in England, but it was still considered a scandal, something to be whispered about behind fans and monocles.

Writers like Jean Lorrain and Marcel Proust turned that secrecy into literature. Lorrain, flamboyant and fearless, filled his stories with dandies and degenerates who looked suspiciously like his real-life lovers. Proust, ever the observer, transformed the hidden world of queer Paris into something eternal — a labyrinth of longing, jealousy, and memory. In À la recherche du temps perdu, the delicate veneer of respectability cracks just enough for us to glimpse the human heart beneath.

It’s hard not to see the Belle Époque as a masquerade. So much depended on disguise. The dandy in his tailored suit and the courtesan in her pearls both played at performance; so did the lovers who found ways to exist within it. Oscar Wilde understood this better than anyone. When he arrived in Paris after his imprisonment, broken but still magnificent, the French decadents adored him. To them, he was both saint and warning — the martyr of beauty, the victim of hypocrisy.

In those same years, women like Natalie Clifford Barney were hosting salons on the Left Bank where sapphic love was celebrated rather than hidden. Barney’s home on Rue Jacob became a sanctuary for writers, artists, and lovers — Colette, Renée Vivien, Romaine Brooks — women who refused to apologize for their desires. Their world shimmered with elegance and defiance. They lived as though freedom were a kind of art form.

But the same century that produced the cancan and Art Nouveau also gave rise to sexology — a new “science” eager to categorize every form of human difference. Doctors and moralists wrote of “inversion” and “degeneracy,” reducing love to pathology. And yet, in their obsession with labeling, they inadvertently gave queer people something precious: a vocabulary. To be called “homosexual” was to be defined, yes, but it was also to be seen. From that fragile recognition would grow an identity, and eventually, a movement.

I sometimes think of those early decades as a paradox — a time when shame and beauty danced together. In the art of Beardsley’s ink drawings, in the languid poses of von Gloeden’s photographs of Sicilian boys, in Wilde’s tragic wit and Gide’s confessions — we can still feel the pulse of lives lived in secret but not in silence.

By the summer of 1914, the champagne had gone flat. The same men who once kissed behind stage curtains marched to the trenches of the Marne; the same women who hosted salons sewed bandages and waited for telegrams. The Great War tore through that shimmering world like a blade through silk. When it was over, the Belle Époque was gone, its optimism buried beneath the mud of Flanders. But the loves and longings it had awakened did not die. They flickered on — in Berlin’s cabarets, in the novels of the interwar years, in every generation that sought to live honestly within its own desire.

Looking back now, the Belle Époque feels impossibly distant — all powdered faces and gaslight. But its queer history feels intimate. These were people who invented ways of being when none yet existed. They loved in shadows and created beauty from the tension between fear and joy. Their courage was quiet but revolutionary.

When I think of them, I think of that Paris light again — soft, forgiving, a little melancholy. It falls evenly on the lovers walking arm in arm and the lonely poet at the café window. It reminds us that beauty and truth have always been companions of the outcast, and that even in an age of repression, love has a way of making itself seen.