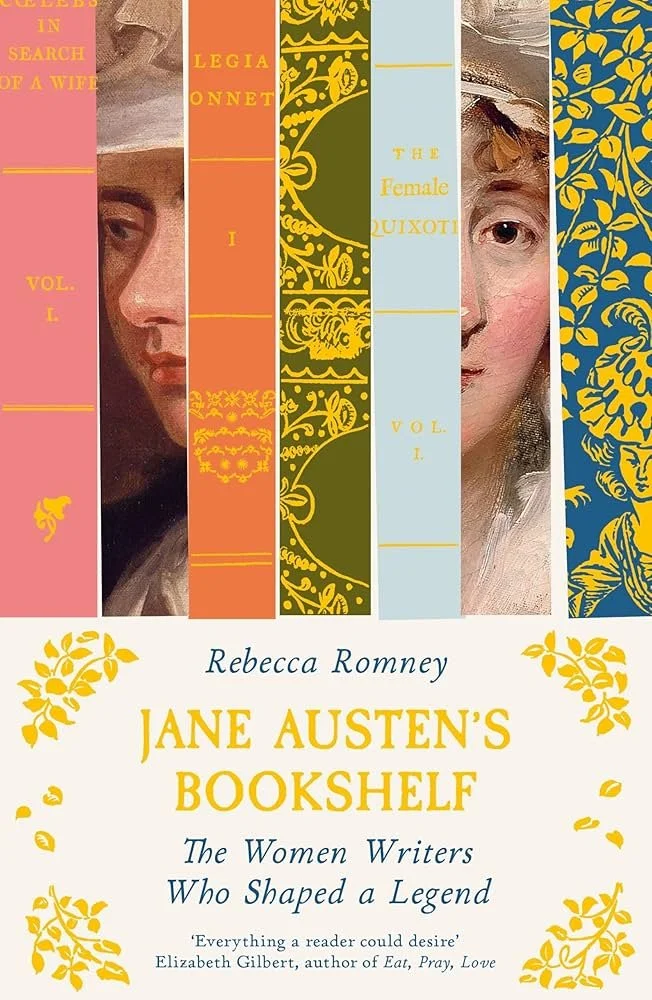

A review of Jane Austen’s Bookshelf by Rebecca Romney

Jane Austen’s Bookshelf sets out to explore the forgotten women writers who inspired Austen, but ends up delivering more personal storytelling than critical substance.

Rebecca Romney offers a promising premise—reintroducing authors like Frances Burney and Ann Radcliffe as key figures in Austen’s literary world—but leans too heavily on speculation and sweeping claims without the depth or evidence to support them. The book is framed as a literary exploration, yet it often reads like a series of essays fueled more by admiration than analysis. As a result, the connections to Austen feel tenuous, and the insights shallow.

Even more distracting is Romney’s repeated focus on the rare book trade. Page after page is filled with anecdotes about tracking down obscure editions, auction prices, and the logistics of antiquarian bookselling—topics better suited to a dealer’s memoir than a work of literary history. While these behind-the-scenes glimpses into the world of rare books may fascinate collectors and industry insiders, they add little to the book’s stated goal of situating Austen within a network of female predecessors. Instead, they repeatedly pull the reader away from the promised literary conversation and into the minutiae of commerce, making the book feel uneven and misdirected.

In the end, Jane Austen’s Bookshelf is a curious hybrid: part homage to overlooked women writers, part personal meditation on the joys and frustrations of book collecting.

That hybridity could have been an asset if the balance had been more carefully struck—if Romney had woven her trade anecdotes into a sharper argument about preservation, canon-making, or the economic histories of women’s writing. Instead, the emphasis falls on memoir, leaving the literary analysis thin and unsatisfying.

For Austen fans, this means the book rarely delivers on its central promise. Readers looking for fresh insight into how Burney, Radcliffe, or Charlotte Smith shaped Austen’s imagination will find little beyond gestures and summaries. For students of literary history, the absence of close reading or critical depth makes the work frustratingly superficial. And for general readers, the enthusiasm may charm in places, but the lack of focus will likely leave them disengaged.

Ultimately, Jane Austen’s Bookshelf may find its truest audience among rare book enthusiasts who enjoy the romance of hunting down elusive volumes. But as a study of Austen’s literary inheritance, it misses the mark—substituting admiration for argument, anecdote for evidence, and commerce for criticism. The result is a book that, despite its intriguing premise, never quite decides what it wants to be.